The case study for DISTURBED HARMONIES [ANTHROPOCENE LANDSCAPES] focuses on a Stalinist dam project and Hungary’s first environmental initiative. Against the background of an expanding technosphere, it touches on underground filmmaking, regime change and conflicts between democratisation and nation-building.

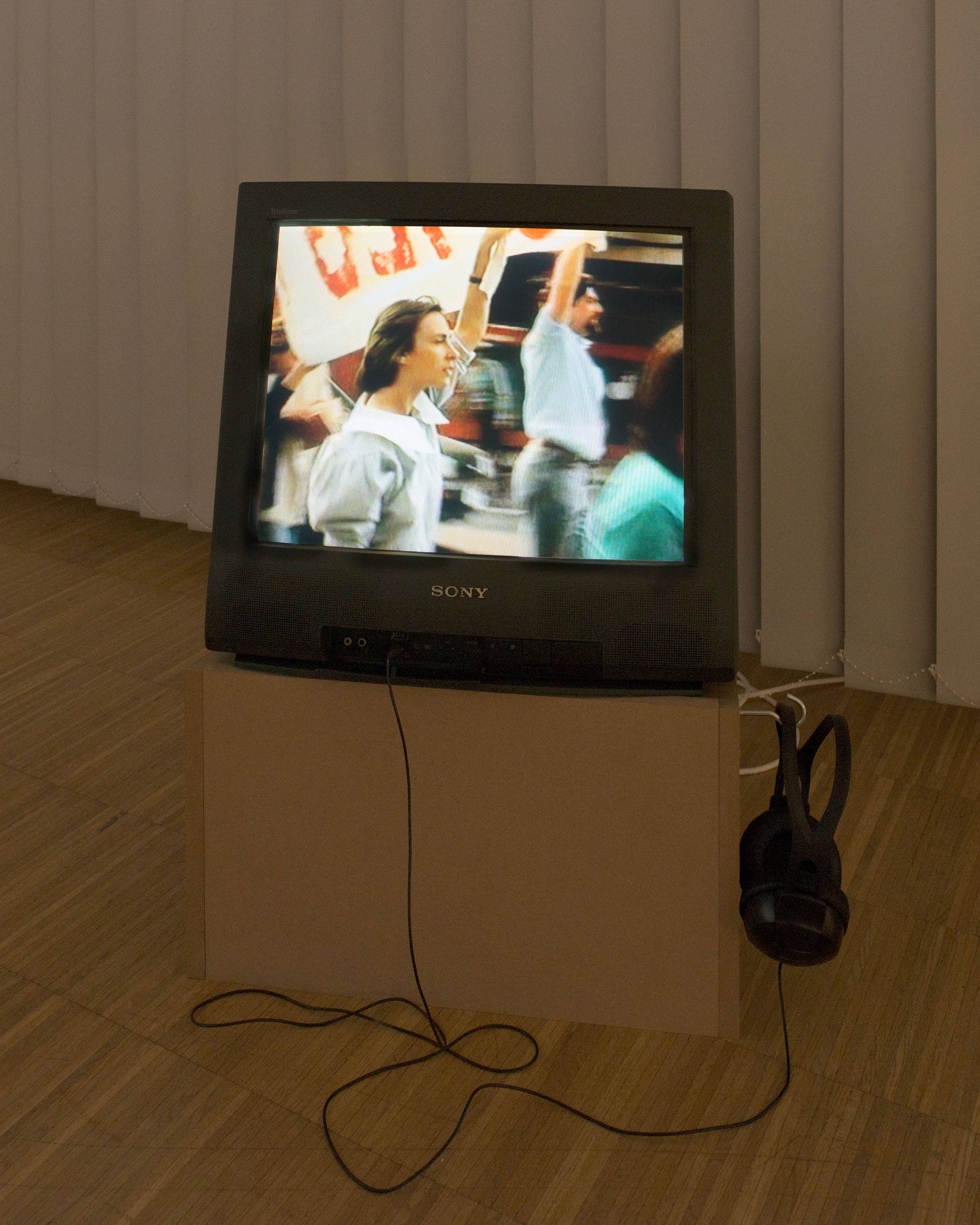

Axel Braun, Discourse Analysis (Protest), 2016

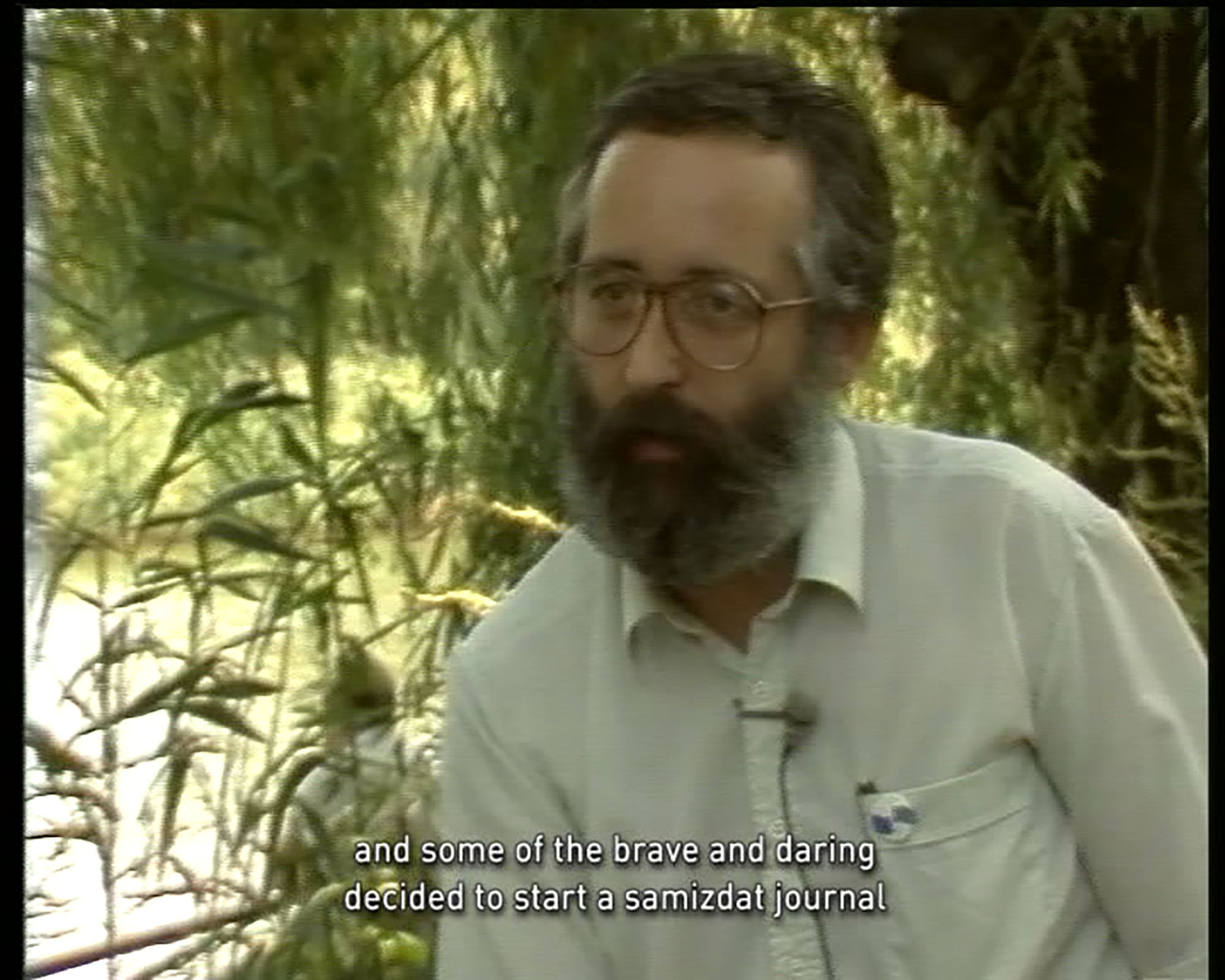

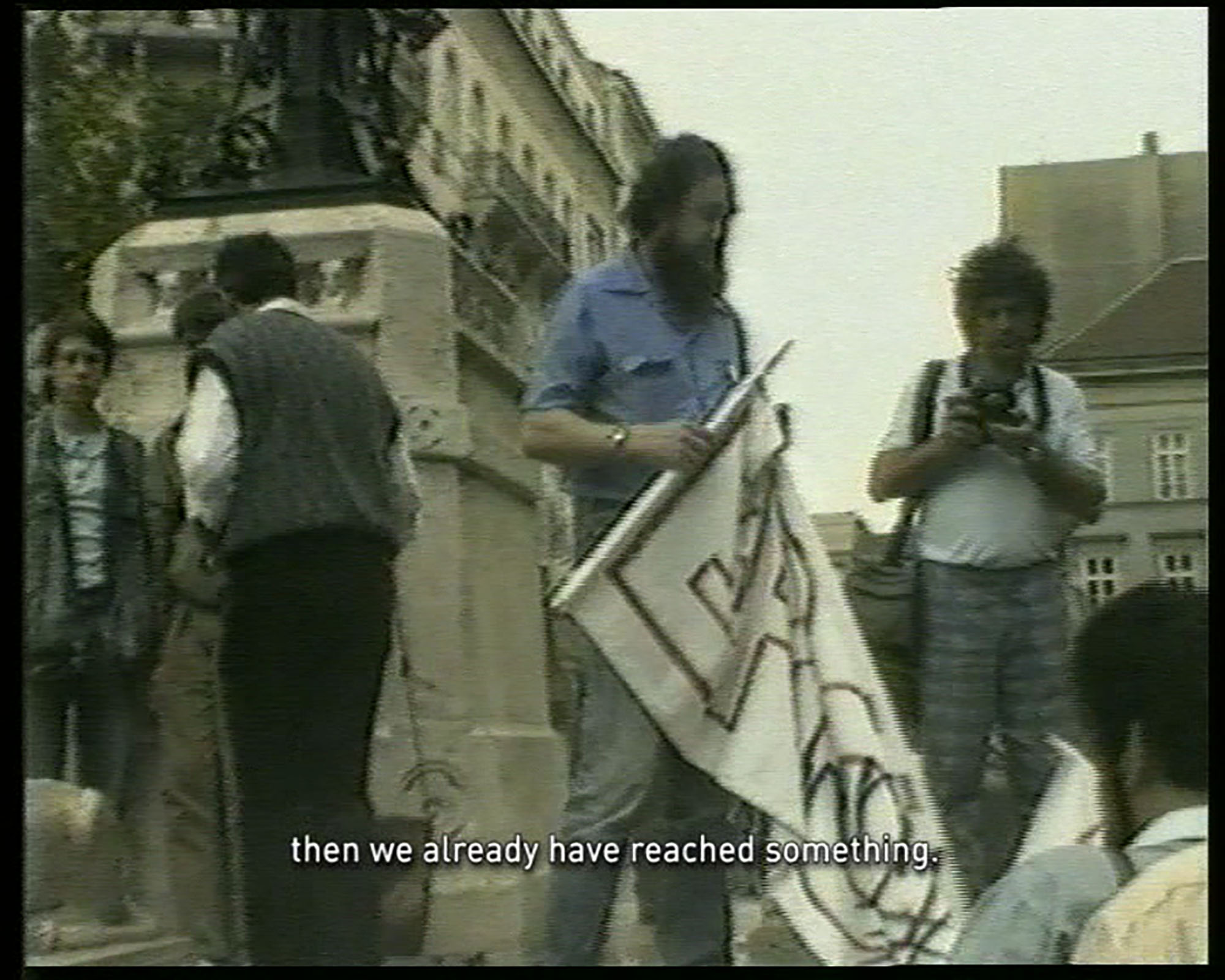

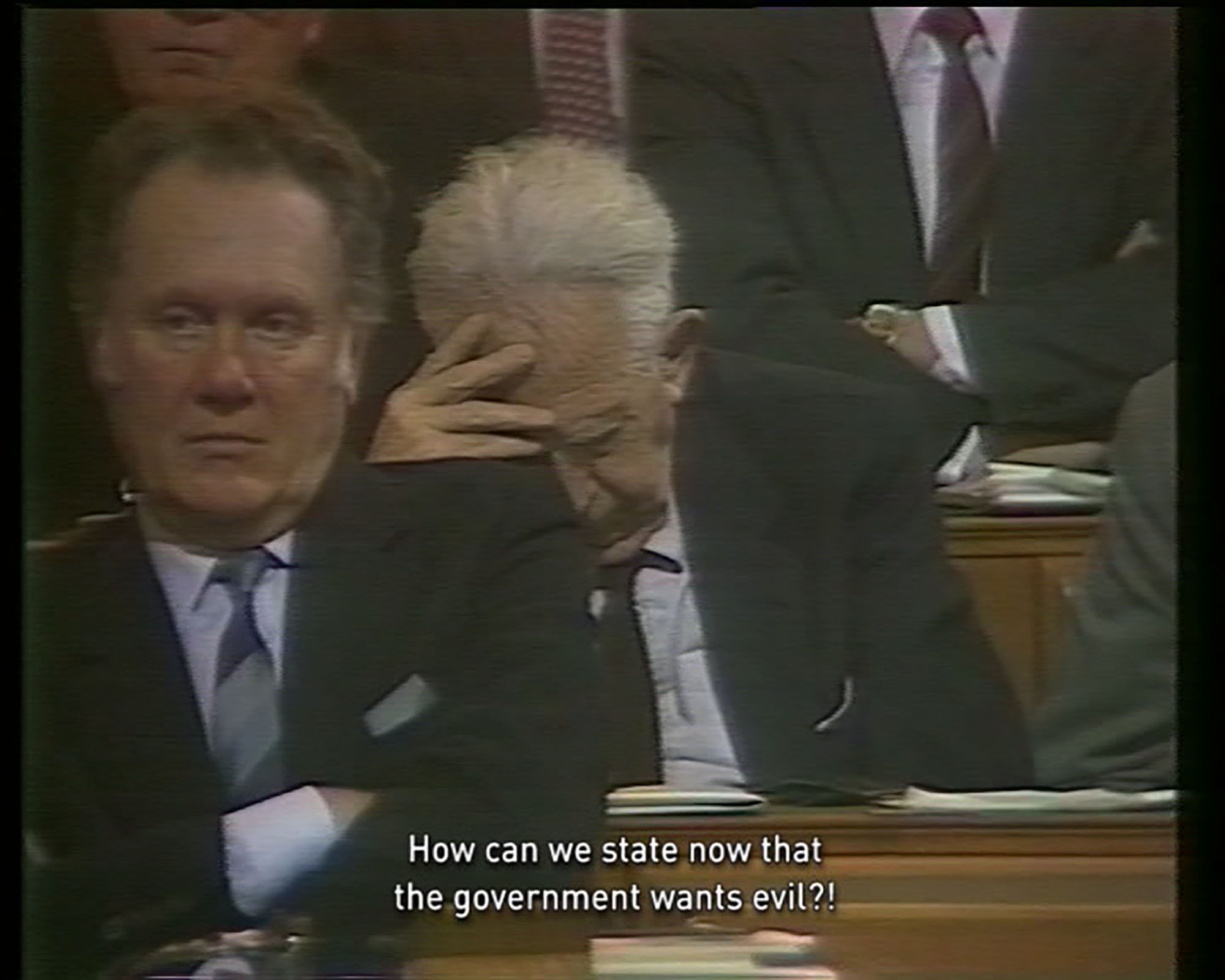

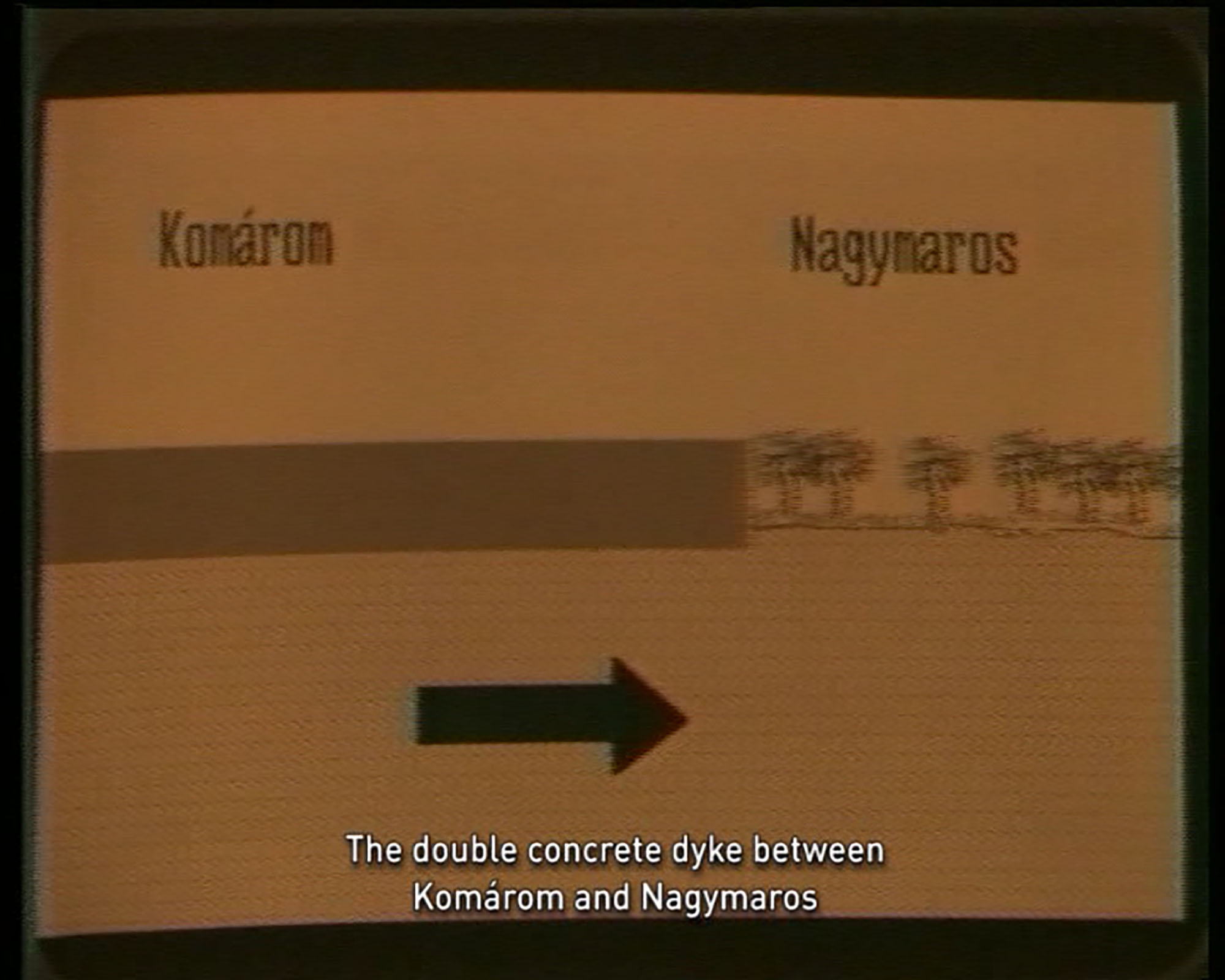

Excerpt of A műtargy (The Object), a documentary by Fekete Doboz [Black Box] about the Gabcikovo-Nagymaros controversy and the activities of Duna Kör, film collection of Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives, Budapest. Copyright by Fekete Doboz, 1988

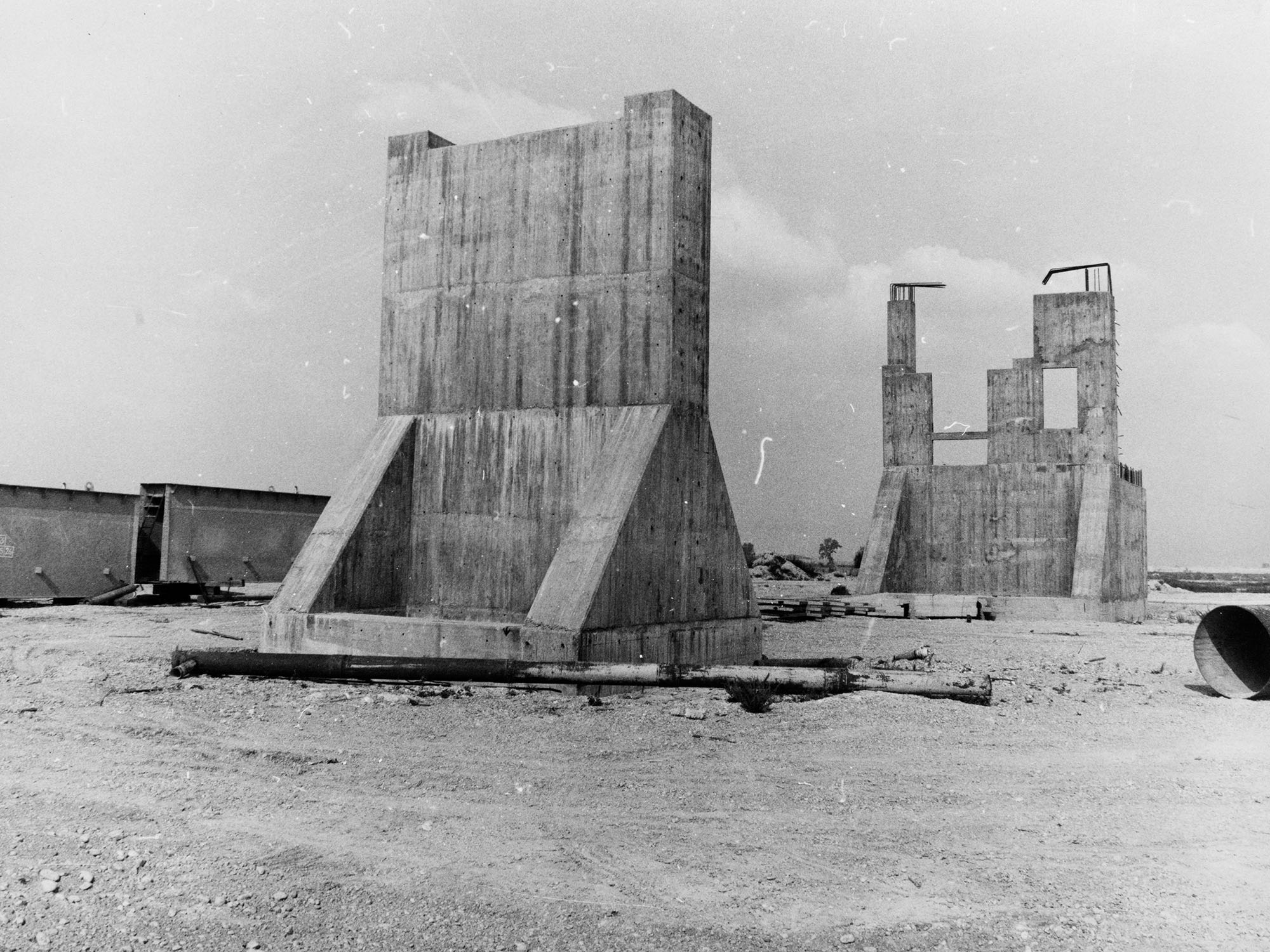

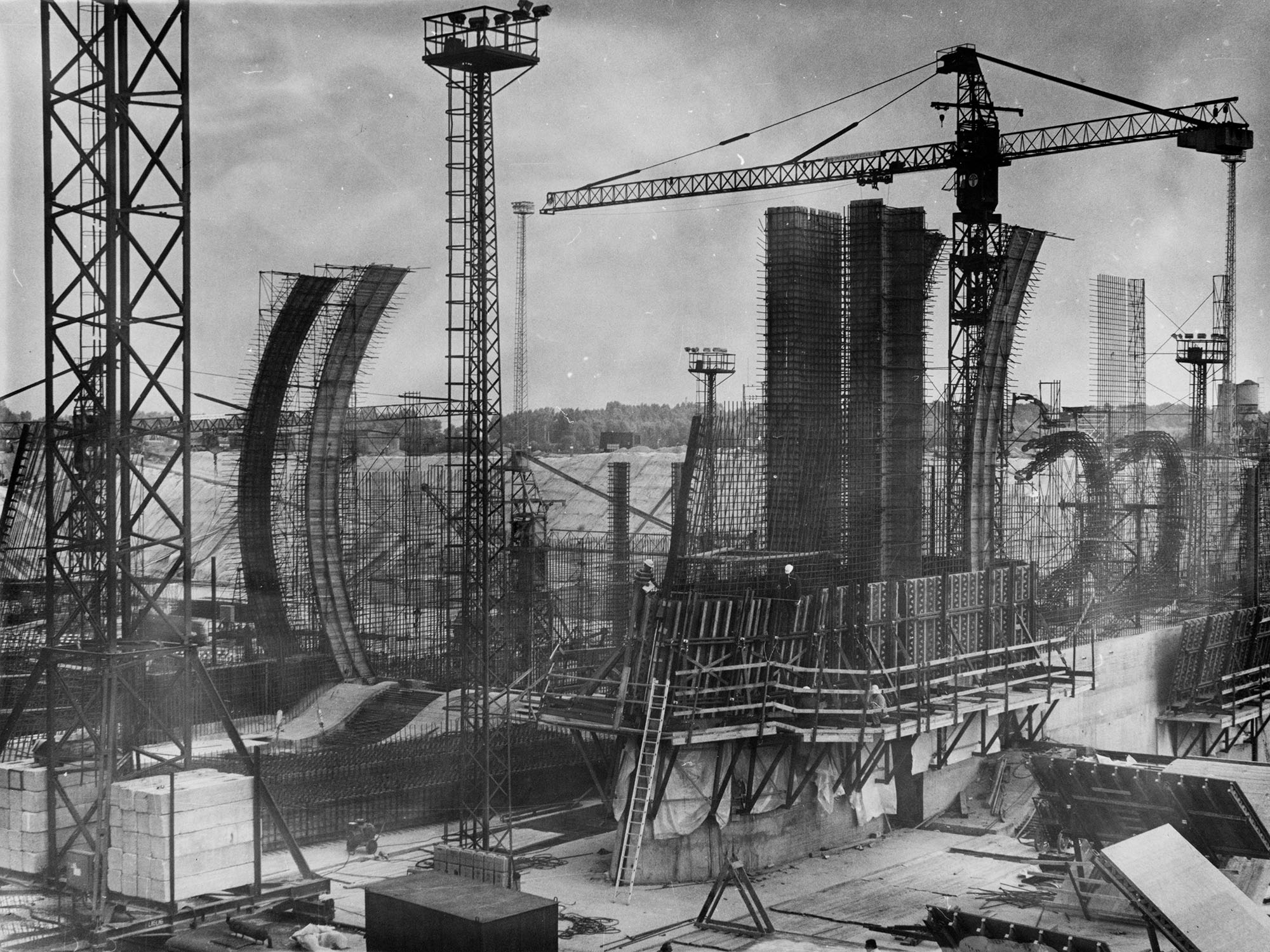

Környezetvédelmi és Vízügyi Levéltár, Reproduction: Axel Braun, 2016

FullHD video, 0:20:00, still

Axel Braun, Video 01 (Danube Bend), 2015, FullHD video (excerpt)

The video shows the place where the Nagymaros dam would have crossed the Danube bend.

‘Committee secretary János Berecz . . . spoke of a ‘certain group’ which was ‘moving in the direction of some kind of opposition’. [1]

At first glance, the case study tells the story of a civic movement that successfully opposed an authoritarian regime. However, it also provides an ideal example for the complex processes and debates that characterise the developments of living spaces in an expanding technosphere. Meanwhile, many of the landscapes at stake can only survive with the technological support of the dams that have almost destroyed them. Furthermore, the case study reflects European integration and illiberal tendencies in Central and Eastern Europe.

It revisits the unresolved controversy about the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Dam System, a disputed infrastructure project that has been partly established along the Danube in Hungary and Slovakia since 1977. The project traces the activities of Duna Kör (Danube Circle) – one of the first environmental initiatives in Central and Eastern Europe – and its substantial role in the change of the Hungarian regime in 1989.

Video footage from the 1980s and early 1990s by documentary filmmakers Ádám Csillag and Fekete Doboz (Black Box) provided the departure point for further archive research and my photo and video productions. I have presented the resulting mixed-media essay in an exhibition at Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives in Budapest.

It was complemented by Politicised Landscapes, a collateral programme with talks and film screenings that I organised together with translator and research assistant Szilvia Nagy.

_________________________

[1]

“B-WIRE / 02-JUN-86 04:59,” 2 June 1986. HU OSA 300-40-1: 276/3; Records of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Institute; Donald and Vera Blinken Open Society Archives at the Central European University, Budapest

At the time of the statement János Berecz was a member of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party and the central committee secretary for ideology. He was seen as a possible successor of János Kádár.

Környezetvédelmi és Vízügyi Levéltár, Reproduction: Axel Braun, 2016

Axel Braun, Discourse Analysis (Landscape), BETA SP edited and transferred to DVD, 2014 (excerpt)

Decomposing raw material by underground filmmaker Ádám Csillag showing the Szigetköz before the ecological disaster following the deviation of the Danube in 1993. Ádám worked on the two documentaries Dunaszaurusz I & II for more than ten years since 1984. I have digitised significant parts of Ádám‘s VHS and BETA SP tapes in the framework of this case study.

Axel Braun, Video 02 (Szigetköz), 2015

FullHD video, 00:12:00 (excerpt)

FullHD video, 0:12:00, stills

Galeria Centralis, Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives at Central European University, Budapest

2016, March 13 – May 1

Discourse Analysis & Video 03 (Gabčíkovo)

Galeria Centralis, Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives at Central European University, Budapest

2016, March 13 – May 1

The scheme for the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Dam System in Hungary and Czechoslovakia consisted of dams and canals that were to redirect and alter the Danube drastically on a stretch of about 200 kilometres, according to a bilateral agreement. They were to dry out Europe’s last inland delta, the Szigetköz, and place a dam in the Danube Bend, an iconic landscape of national identification. This prospect mobilised Hungary’s first environmental initiative, founded by biologist János Vargha in 1984. Initially, the group used Samizdat underground publications. Despite oppression during the early years, the movement kept growing, and the political climate of perestroika made large protests and petitions possible in 1988. One year later, Duna Kör reached its most significant success: the socialist government suspended the construction of the Nagymaros dam, and its democratic successors discarded the project entirely in 1991.

Even touching on the topic was seen as political suicide in Hungary for decades. It was so closely related to the events of regime change, and many politicians in post-socialist Hungary had built their careers on fighting the dam. So did Viktor Orbán and the FIDESZ movement that joined the environmental protest in 1988. However, these „Young Democrats“ have remarkably changed their agenda, so the debates were reopened in 2016.

While not building the dam became a symbol for democratisation in Hungary, completing the scheme became a symbol for nation-building in newly independent Slovakia, aiming to achieve energy autonomy. Consequently, Slovakia continued alone in the 1990s. The Danube was redirected towards the Gabčíkovo Hydro Power Plant …

VHS & BETA SP edited and transferred to DVD, stills

The material derives from the films A műtargy (The Object) by Fekete Doboz [Black Box] (1988) and Dunaszaurusz I & II by Ádám Csillag (1984–1993), and further material from the filmmakers' archives that has been digitised by Axel Braun in 2015. Selected sequences have been re-edited according to the keywords Pro, Contra, Undecided, Protest, System, Mediation and Landscape.

Axel Braun, Discourse Analysis (Protest), BETA SP and VHS edited and transferred to DVD, 00:24:21

Mass protests against the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Dam System in Budapest, 1988-1989.

Documentaries and unedited material by Fekete Doboz and Ádám Csillag have been re-edited and presented as a seven-channel installation.

Axel Braun, Discourse Analysis (Mediation), BETA SP transferred to DVD, 00:03:54, 2016

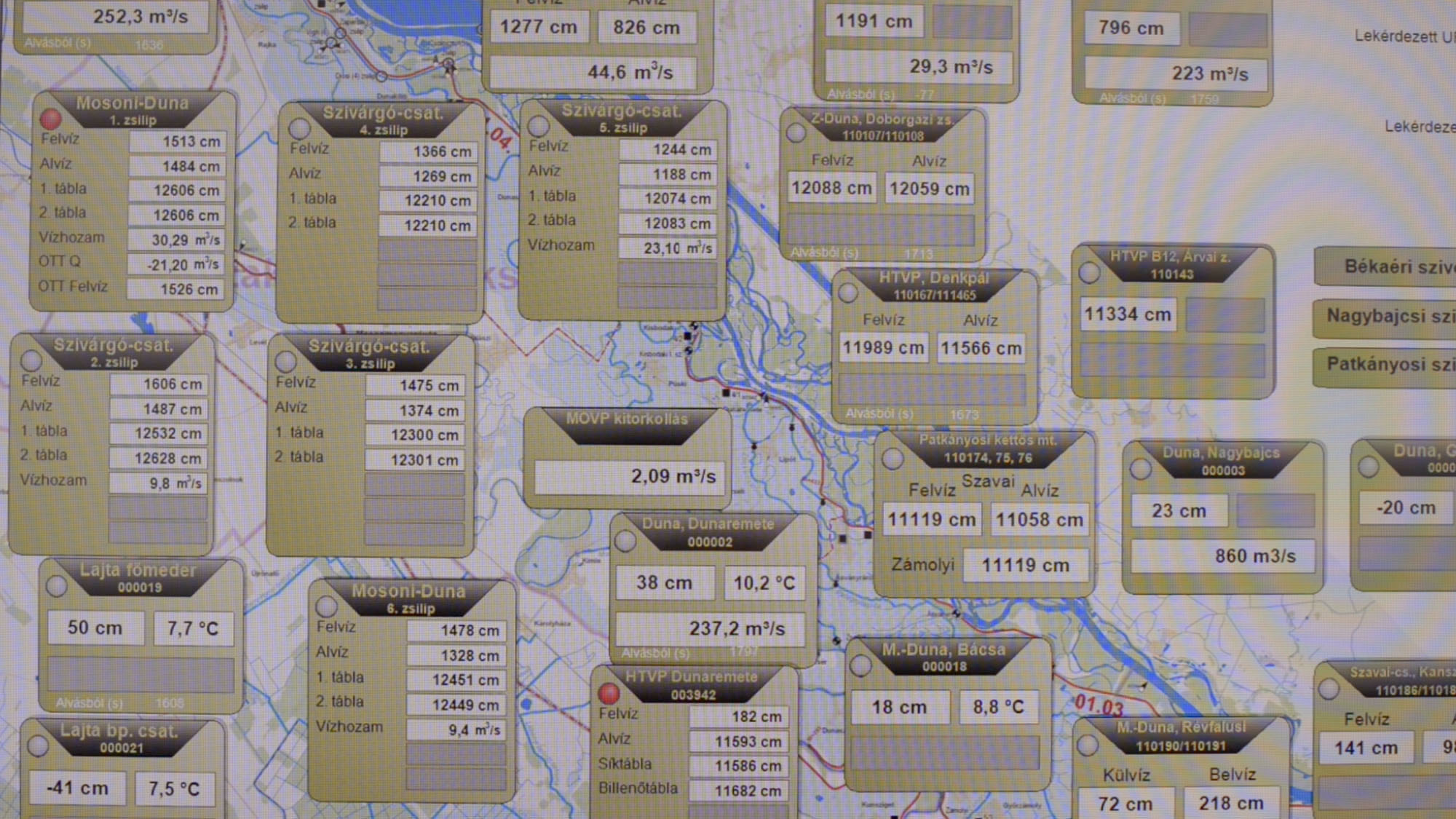

Descriptions of the technological aspects of the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Dam System provided by the Hungarian authorities were featured in Ádám Csillag's Dunaszaurusz I (1988).

FullHD video, 0:21:00, stills

Axel Braun, Video 02 (Gabčíkovo), 2014, FullHD video (excerpts)

FullHD video, 0:07:00, stills

2016, March 13

Galeria Centralis, Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives at Central European University, Budapest

The case study has been presented for the first time at Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives at Central European University, Budapest, from 2016 March 13 to May 1.

The project was only feasible with the relentless support of research assistant, translator and project manager Szilvia Nagy.

Kunststiftung NRW and Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives supported the exhibition. A Visegrad Scholarship at the Open Society Archives (2014) and an Artist-in-Residence Fellowship by the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) and Visual Studies Platform (VSP) at Central European University (2015/16) supported the artistic research project.

POLITICISED LANDSCAPES, a collateral programme with presentations, panel discussions and film screenings, was organised to extend the exhibition's focus. CEU IAS, VSP and Kunststiftung NRW supported the series of events.

More detailed online documentation is provided at