Axel Braun, View from Sant'Erasmo towards Venice, 2024

ABOUT THIS PROJECT

During the past fourteen years of working on Anthropocene landscapes, I have developed an increasing interest in the broader historical context of humanity's emergence as a geological force. What worldviews and concepts of nature have laid the groundwork for the unprecedented exploitation and destruction of natural systems that have occurred since the Industrial Revolution? My fields of interest expanded from resource extraction, colonialism, and the slave trade to pandemics and the development of the modern banking system.

Machina Mundi (XV century clock work, Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice), UltraHD video, 2024

PROLOGUE

Machina Mundi is a worldview that emerged during the late medieval period. It envisions the universe as a mechanism where all processes and events unfold according to a calculated plan. Throughout the Renaissance, humans gained knowledge and confidence, striving to understand these processes in order to influence and master them. Later, the Enlightenment intensified a conceptual dualism between humanity and nature. Humans, as rational subjects, were to understand nature as an object of knowledge and control. Johann Gottlieb Fichte observed a continuing strife between Reason and Nature, in which the human rational will eventually dominate.

ABER ES SOLL UND KANN DER EINFLUSS DER NATUR IMMER SCHWÄCHER, DIE HERRSCHAFT DER VERNUNFT IMMER MÄCHTIGER WERDEN.

[…but the influence of Nature can and ought to be gradually weakened, the dominion of Reason constantly made more powerful…]

_____________________________

Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Einige Vorlesungen über die Bestimmung des Gelehrten (1794), in: Ders., Gesamtausgabe der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Bd. 3, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1966, p.45

[Johann Gottlieb Fichte, The Vocation of the Scholar, translated from the German by William Smith, London: John Chapman, 1847, p.41]

BEAUTY, BRUTALITY, SCIENCE AND ATROCITY

Nature at large will adapt to any form of anthropogenic devastation. Eventually, humans will suffer the most from the processes that their species has triggered. Humanity has repeatedly produced unprecedented creativity with impressive and often beautiful results. Unfortunately, the unintended consequences can be incalculable, and many achievements benefit just a chosen few, especially when they have been built on the backs of others.

Often, harshly contrasting processes are deeply entangled. Beauty is preconditioned by brutality, and scientific splendour coincides with atrocities.

This case study approaches the city as a fragile relict of a glorious past. It is a sample that enables us to observe the fundamental structures and vulnerable points of global networks.

ON OTHERING

We need the other to define ourselves. Societies distinguish between their members and those who are excluded. However, successful isolation from foreign influences has been an exception in human history. Empires, in contrast, follow an inherent logic of expansion. This makes definitions of belonging even more vital for those who aim to assert and sustain power. To oppress, exploit and extract, it is necessary to know your kin and to exclude the rest from the rights that you claim for yourself. At the same time, offering purpose and justification for the profiteers is crucial. Nobody wants to be the bad guy. Thus, it is common practice to define moral standards accordingly. Sometimes, that which is believed to be good is evil.

MYTHS OF VENICE

Much has been written about the virtues and achievements of La Serenissima Repubblica.

Venetian art and architecture, as well as its political and economic institutions, have been idealised and imitated worldwide. Nevertheless, the Myths of Venice are omnipresent in the symbols and allegories of the city’s historical artworks. They result from repeated entanglements of fact and fiction that aim to consolidate power through what later would be called cultural hegemony. Throughout the medieval ages, Venice refrained from theft and looting, at least according to contemporary accounts. Since the early modern period, it proudly presented (alleged) war booty as a means of claiming ascendancy. At the same time, maintaining diplomatic relations with friends and enemies was a precondition for a successful mercantile network.

Slave (Baldassarre Longhena with G. Le Court, M. Barthel, F. Cavrioli and M. Fabris ‘The Pesaro Funerary Monument’, 1665–69, Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice), UltraHD video, 2024

FOUNDATIONS OF WEALTH

From the early Middle Ages, the capturing, buying, shipping and selling of slaves was a substantial pillar of the emerging trade empire. While enslaving fellow Christians was already prohibited, pagan Slavs from the Balkans were among the first to be traded across the Mediterranean. At the time, there was a strong demand in Middle Eastern and North African societies for subjugated workers and warriors. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, slavery became less accepted in Romance-speaking Europe, but the devastating effects of the plague resulted in a return to earlier standards.

From the Renaissance onwards, artworks depicting African slaves and servants confirmed their owners’ status. Nevertheless, numerous wills illustrate that it was a widespread practice to free slaves after their masters’ death – which ensured them both the convenience of slavery during their lifetime and an unhindered transition to heaven.

A CURRENCY

Murano’s glass workshops created a monopoly for Venice that endured for centuries. When the trade in luxury goods declined in the Early Modern Age, the industry was saved by a rising demand for glass beads. Beads were a traditional currency for many Indigenous communities in Africa, Asia and the New World. Thus, Europe’s emerging colonial powers and their slave traders recognised the advantages of Murano’s knowledge and production capacities. While Venice had lost its prominent position in world trade, it could still benefit from the networks that were being created by its successors. The most notable of these was the triangular trade that connected Europe, Africa and the Americas with logistical efficiency. For more than two centuries, Venice was the leading supplier of the glass beads that archaeologists occasionally find in unmarked tombs scattered around the globe.

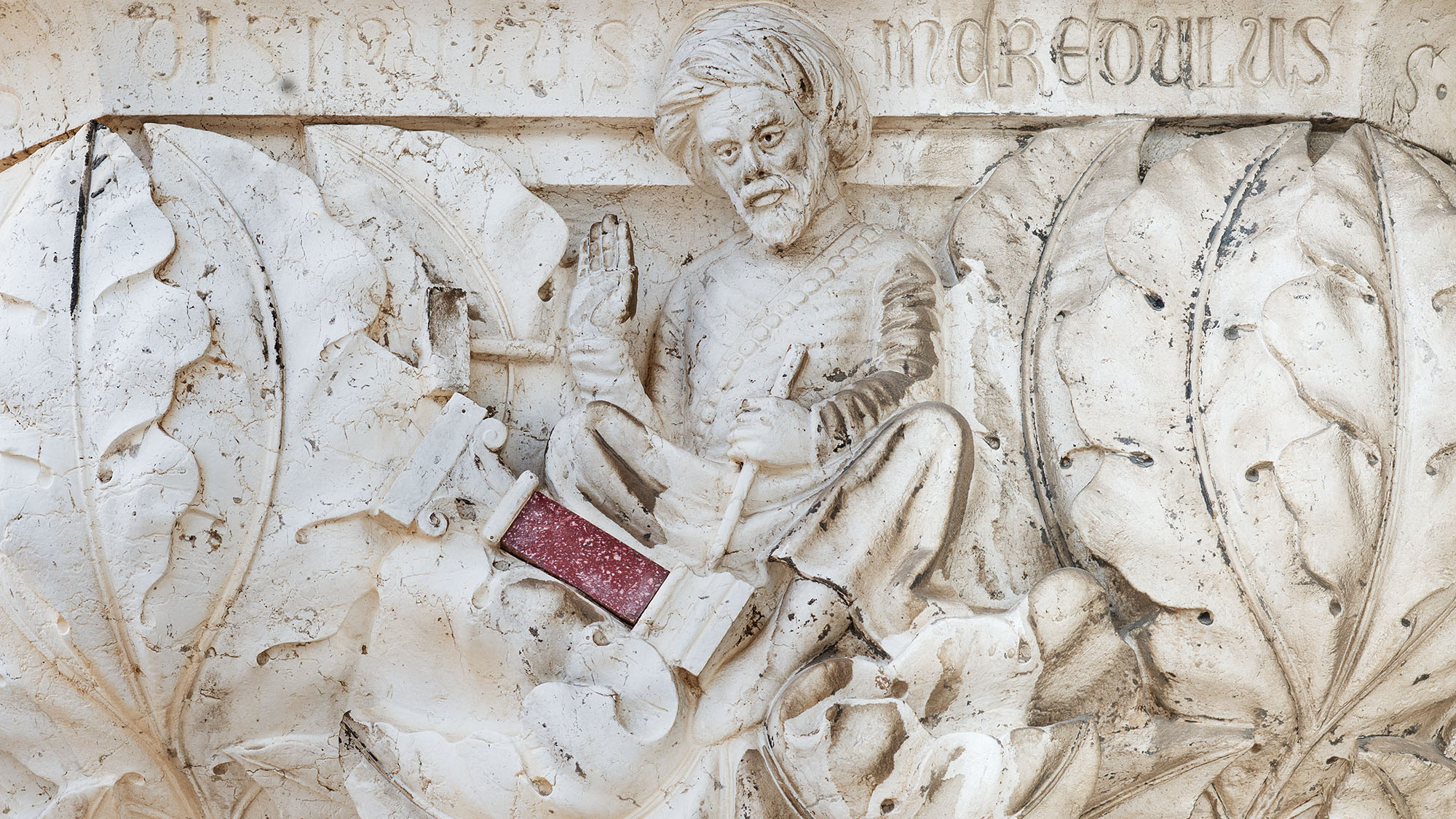

Stone Mason’s Capital (Copy by Giovanni Zamolo, The Four Crowned Saints and their Apprentices, 1878, original: 1342–1348, Palazzo Ducale, Venice), animated 3D-model, UltraHD video, 2024

RESOURCES AND DEPENDENCIES

While its position on the lagoon provided security from its enemies, it imposed countless other challenges on the growing metropolis. Thus, Venice has always depended on the Terraferma and exchange with the outside world. Analogous to its expansion of power, controlling trade routes, battling enemies and establishing colonies became vital requirements. The city’s built environment and material culture mirror these processes. Construction materials, know-how and a workforce needed to be imported—sometimes through trade and persuasion and sometimes through theft and coercion.

THE STONES OF VENICE

Pietra d’Istria is just one example of this dependency. Without these exceptionally durable stones that have risen from the sea, the city would have vanished long ago. Almost every cultural practice that was mastered in the lagoon would have been unthinkable without imported ingredients, from wood and stone to metals and minerals. Thus, exploring and extracting were added to the list of the vital skills cultivated in Venice.

RISE AND FALL

Some of the oldest traces of human existence in the lagoon have been discovered on the islands of Torcello. Around the year 1000, they were more densely populated than Rivo Alto was at the time. However, Torcello declined in analogy to the rise of Venice around Rialto and San Marco. Until the end of the Medieval Ages, the population had shrunk drastically, buildings were demolished, and construction materials were reused elsewhere.

Currently, rising sea levels due to climate change threaten the Venetian islands.

Back then, the lagoon was becoming marshy due to sediments and the freshwater influx of the mountain rivers. The resulting problems for navigation and the spread of malaria sealed Torcello’s fate.

THE LAST REFUGE

The lagoon's barene are a last refuge for fish and birds. These marshlands have developed on the very sediments that became a challenge in the Middle Ages. The constant interplay of erosion, flooding, and silting is typical in a natural lagoon. In a built environment that countless humans use and navigate each day, there is no room left for transformation. The remaining sandbanks must be artificially reinforced to protect them from the waves of the Vaporetti, while the waterways must be regularly dredged to maintain their navigability.

THE ROOT OF ALL EVILS

Since the Middle Ages, the Venetian authorities have established expert commissions to find solutions to the persistent silting of the lagoon. Soon, the Brenta River, which originates in the High Alps, was identified as el principio de tuti i mali. Before long, the Piave and other rivers with estuaries in the lagoon were targeted as well.

For over three centuries, efforts have been made to manage the situation. What began as a trial-and-error approach evolved into profound expertise in hydrological engineering. Rivers were canalised or entirely diverted. Islands were reinforced and connected through land reclamation. The canals within the lagoon were dredged and, in other places, obstructed. Until the end of the 17th century, the larger rivers were banned from the lagoon. The estuary of the Brenta was relocated approximately thirty kilometres to the south, close to Chioggia. The Brenta Nova is a straight canal. At its end, only a dike prevents it from flowing into the lagoon.

Former Delta of the Brenta River (near Fusina), UltraHD video, 2024

THE TECHNOSPHERE

The former Brenta Delta receives only a small portion of the river’s discharge. At first glance, the marshland seems like a romantic, natural landscape. However, it is shaped by roads and hydrological devices and plays a significant role in purifying the lagoon.

The existence of this landscape depends on human oversight and intervention.

THE FATE

The empire has been reduced to the crumbling remnants of its capital. The beauty and glorious history of Venice are its final assets. After centuries of trading the most exclusive goods, the city sells its scenery like a commodity. Will it eventually be choked by over-tourism or become an isolated resort that is only for those who can afford it?

Whatever happens, there are other, more substantial threats. The cultural skills that once facilitated the unlikely rise of a city built on water have developed exponentially during the last centuries and created an ever-expanding technosphere. Venice is an entirely built environment. It is increasingly facing the devastating consequences of human interference in the Earth system. The lagoon has become a scale model for the global challenges of the Anthropocene.

The Fate (Madonna del Monte), UltraHD video, 2024

CREDITS & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My residency at the Centro Tedesco di Studi Veneziani in Venice from April to June 2024 was the perfect opportunity to delve into this new aspect of my research.

During this time, I received a scholarship from the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media. I am also very grateful for a project grant from the Dr. Christiane Hackerodt Kunst- und Kulturstiftung.

Furthermore, I want to thank all institutions that granted me access to their holdings and collections.

I am also grateful to Cristina Baldacci, Noemi Quagliati, Pietro Daniel Omodeo, Wolfgang Wolters, Michael Knapton, Christina Hainzl, Armin F. Bergmeier and Luc Wodzicki for their invaluable information and support, as well as to Alexander Cattaneo, Sabine Engel, Fabien Vitali, and my other co-fellows, who provided me with inspiring input during our conversations.